Testing and persistent state

Jordi Pradel, June 17, 2022

The recipe consisted of (1) setting the initial known state, (2) executing the functionality to test, (3) collecting and asserting over results and (4) collecting and asserting over final state

In our previous post about software testing, we gave the perfect receipt to test something even in the presence of state. Armed with that, we were able to test pure functions and “functions” whose responses depend on some state. I left you with the promise of talking about getting the current time, reading or writing from files and some other nasty side effects. We will now focus on reading from and writing to some persistent storage. Here we go.

Let’s talk about state, again

Take 1

You remember the silly example of our test of MemoryAdder, don’t you? Its linked up there. I wait for you just here. Done? Ok.

So, now imagine you have a database (of any kind) where you store your valuable data. A database basically keeps state for as long as you want and (probably) indexes it to allow you to query it in fancy ways. Now, let’s say you have a “function” that saves something to a database. I’m assuming something similar to an sql database here, and talking about rows, etc. It doesn’t matter, for the purpose of this article. We could be speaking of a document database and its documents instead.

Note: You wouldn’t put Connection as a parameter of this function? Nice, me neither. Stay with me on this one. If I manage to remember what I’m just saying, which I probably won’t 🐠, I plan to write about dependency injection using this very example as our starting point.

fun updateUserLastVisit(

conn: Connection,

userId: Long,

lastVisit: Instant

): Boolean {

val updatedRows =

conn.execute(

"update users set last_visit = ? where id = ?",

lastVisit,

userId

)

return updatedRows > 0

}

To test this method you simply:

- Prepare an actual database instance nobody else will use, tipically running it in the same computer the test runs in

- Follow the recipe

So, let’s tryIt won’t work this time, keep reading for a better solution:

// 1. Set initial state

val userId = 23L

val userName = "John"

conn.execute("insert into users(id, name, last_visit), ?, ?, null", userId, userName)

// 2 and 3. Execute the method and assert

val lastVisit = Instant.now()

val wasUpdated = updateUserLastVisit(userId, lastVisit)

assertTrue(wasUpdated)

// 4. Collect the final state and assert

val endState = conn.execute("select last_visit from users where id = ?", userId).first()

assertEquals(lastVisit, endState)

Nice, no? Nope. You may already know me. Sparing English not being my native tongue, when I say something I mean it. And I said, I quote, “Collect the final state”. That’s not what I did here. Red flag! 🚩Alert! 🚨 Why? Well, I just checked the value I assumed I was modifying, I didn’t collect the (whole) end state.

Side effects everywhere

What’s the problem with that, you say? After all, some projects out there forget to test the final state and many of the ones that don’t, check it like we did above. The problem, as you may already see, are… unintended side effects.

What if updateLastUserVisit also updates the last_updated column? Would that be intended (and missing from our test) or unintended (and passing our test wrongly)? What if it deletes the row in some particular case? Or if it affects some other row?

Take 2

So, let’s fix that step 4Only step 4, here. See the complete solution later.:

// 4. Collect the final state and assert

data class User(userId: Long, userName: String, lastVisit: Instant)

val endState =

conn.execute("select id,name,last_visit from users order by id"){

(i, n, lv) ->

// oh dear, how I miss Scala's tuples here...

User(id, n, lv)

}

assertEquals(listOf(User(userId, userName, lastVisit)), endState)

One intesting side benefit of checking the final state this way is that the auxiliary method we need to retrieve the final state is always the same, no matter the particular test at hand. That saves some nice hours of coding tests.

But why would we only check the users table? What about other tables? Sure, you could check absolutely all the end state if you want. I’ve done that sometimes. Just balance the effort against the probability a function supposed to use one table manipulating the data in another one.

And what about the performance of querying all the rows in a table? This database is one you never share, remember? And the initial state it has is only the state you set it to have in the first step of our recipe, right? So, yes, you can probably query all of the rows in your database; in this example, it is just one.

Now it’s done, right? Oh, you have seen it, right? No? Again, let’s do what we said, and we said “set initial state”. Inserting a single row in a database is not stting a known initial state. There may be other rows there. And, hopefully, our rewritten step 4 would detect that and our nice test would fail.

Take 3

So let’s fix that as well. Final solution nowI’ll be considering this to be the good solution. Of course, it may have bugs, in which case I would greatly appreciate any feedback.:

// 1. Set initial state

val userId = 23L

val userName = "John"

conn.execute("delete from users")

conn.execute(

"insert into users(id, name, last_visit), ?, ?, null",

userId,

userName

)

// 2 and 3. Execute the method and assert

val lastVisit = Instant.now()

val wasUpdated = updateUserLastVisit(userId, lastVisit)

assertTrue(wasUpdated)

// 4. Collect the final state and assert

val endState =

conn.execute("select id,name,last_visit from users order by id"){

(i, n, lv) -> User(id, n, lv)

}

assertEquals(listOf(User(userId, userName, lastVisit)), endState)

Note: I’m assuming the database structure was fixed. We don’t need to create the users table when we run the test because it is something our code does not change.

An actual database instance nobody else will use?

Those are the words I used. Test your functions using persistent state using “an actual database instance nobody else will use”. There are two main points here.

Use the actual thing

The first one: Use an actual persistent storage. In fact, use the very same persistent storage technology you use in production. You have PostgreSQL 13.7 in production? Use a PostgreSQL 13.7 to store your tests data. Because, why not? The benefits of using the very same technology are crystal clear: there won’t be any difference that causes false positives (code that fails in production but passes all the tests ) or false negatives (code that works perfectly well in production but fails to pass the tests).

I won’t go into details, at least not now, but you can use Docker and other virtualization solutions to run such infrastruture. Just, please, don’t make all developers in your team install a ton of software in order to run all tests in the repo.

Don’t share your persistent state

The other part of that suggestion is about not sharing the state with anyone else. I already hinted about some of the problems I’ve seen when sharing the persistent state used in tests. You don’t want your tests behaviour to depend on whether someone else actions. You want them to always give the same results. Known initial state, exercise the program, collect results and assert, collect final state and assert.

What about the tests in your test suite sharing the persistent state? No! Nein! Ni parlar-ne!

Gollum doesn’t want to share its preciousss… persistent state. Me neither.

You are probably using the same database for all your tests. But you can’t share state between tests. You need to be able to run a single test. You’ll maintain tests and you may remove some of them, or add one test in between existing tests. You can’t afford the result of one test depending on the state left by other tests executed before it. What do yo do? Known initial state, exercise… You know. I mean, following the recipe I gave in the last article, you guarantee each test starts with a known state, no matter what other tests have done before.

Don’t simply take whatever initial state you find while trying to cleanup afterwards.

For some reason, I’ve seen cases where the recipe is different. Instead of setting a known initial state, tests make the effort to leave things as they found them: they clear whatever state they stored during the test. That tries to solve the same problem of one test affecting other tests. But it is flawled. To begin with, a simple failure to properly clean the state could trigger a failure (or worse, a false positive) in an unrelated test of the same suite. Good luck finding out what just happened. On the other hand, whenever a test fails, sometimes it is very nice to see the end state there for you to query. You are welcome.

Concurrency and persistent state in tests

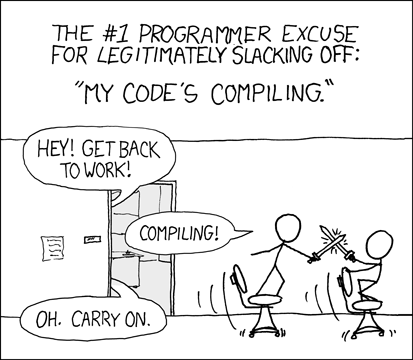

And… what about concurrency? I don’t know yours, but my laptop is much, much powerful than any of the nodes in the production environment that run the code I write with it. Heck, it has more cores than I can remember and long are the days when I could drink I coffee while my previous laptop struggled to compile a big Scala project.

But concurrency is not a trival one to solve, when you have persistent state in tests. Specially not as an afterthought.

So far, we avoided others (developers or the CI server) affecting our builds, by running our persistent storage (e.g. our PostgreSQL) in the same computer where the tests run. And we had the certainty that our tests run in a known state because we set that state ourselves: no test trusted whatever state it found there (from previous test executions or whatever) an it set the wanted, known initial state itself. But now, we may have several concurrent tests doing the very same. So they will affect each other.

The solution to this problem usually is to just not run tests concurrently. Let that small chat app eat that CPU as though there were no tomorrow.

Every other solution depends on the technology you use. For the sake of giving some hint at it, assuming you know a bit about relational databases, we could make each test generate a random unique identifier and, then, create and use a schema or a table with such name as part of the name. Of course, we would need to be able to create such schemas or tables from our test code.

// 1. Set initial state

val userId = 23L

val userName = "John"

val executionId = UUID.randomUUID()

conn.execute("create users-$executionId(...)")

conn.execute(

"insert into users-$executionId(id, name, last_visit), ?, ?, null",

userId,

userName

)

Conclusions

So we are now equiped with the perfect recipe to run tests that use persistent state without any hassle. We played a bit with it and saw what we actually mean when we say “set the initial state” and “collect and assert the final state”. We also saw how to run tests concurrently to take advantage of the large number of cores we have in our laptops nowadays.

But many open questions from the first article remain unanswered. What about testing a function that gets the current time? One that uses random values? What about something that sends HTTP requests to the world?

More on all of that to come. See you soon!